Our first week in Zambia had been productive. The plan for the second week was to leave Lusaka and travel to the Copperbelt province a few hours drive north of the capital. We’d been staying in a cheap and basic guesthouse in Lusaka which, whilst close to NMEC, was not the most restful. By our sixth night there, we’d all had enough of sharing our space with a menagerie of farmyard animals and 4am rooster wake-up calls, so we spent the Saturday night in a relaxed and quiet tented camp a short drive out of town.

We travelled up to Ndola on Sunday with Jacob Chirma, the Ministry of Health official who’d helped us plan last week’s workshop. The drive was a typical example of a busy African highway. One lane in either direction, they tend to be congested with a steady stream of slow moving trucks carrying containers or packed to the gunnels with produce like sugarcane or copper or else are tarpaulin-wrapped. A lot of time is spent overtaking these trucks when the road is clear, which is normally straightforward as the roads are often straight. Drivers also help out with indicator signalling. Right indicator means don’t overtake, whilst indicating to the left on a straight road normally means that the truck driver can see enough clear road for you to pass. It’s tiring driving though, and even the five hours up to Ndola can take it out of you.

On Monday, before we did any work in the region, we needed to meet the head of health for the district to inform him of our work and get his blessing to visit a malaria clinic in the area. We arrived at his office at 8.30am but he was already in a meeting. The district health office compound reminded me of a 1960s science department at a British university – all squat, single storey buildings that looked like the proverbial science block. Strangely, there must have been about 100 vehicles parked outside, making it look like the whole city was visiting.

To buy some time before the director was out of his meeting we went to the Tropical Disease Research Centre (TDRC) at the nearby central hospital. After walking up seven flights of stairs to the sixth floor we were delivered to an office where we would await the deputy director. Clinician, Dr Christine Manyando, arrived a few minutes later and after introductions listened to our story. She’d popped out of a meeting to see us briefly – she told us that she always loves to see Jacob from the Ministry of Health in Ndola – and she immediately decided to gather the rest of the department to talk to us, suggesting that we return that afternoon for a more formal meeting.

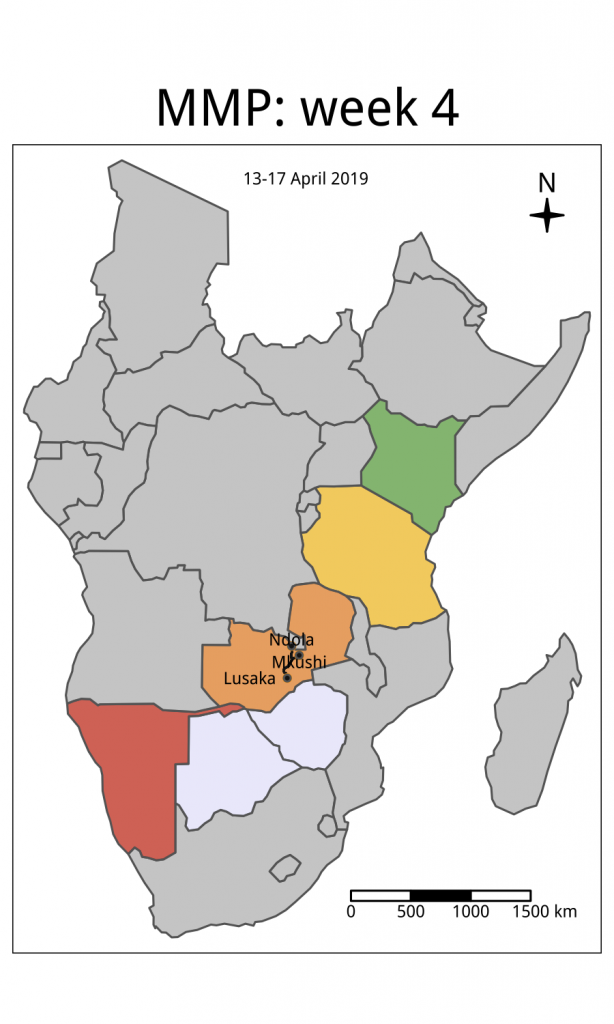

We went back to the district health office and met with the director for 10 minutes. We heard of the work they were doing to halt malaria using bednets and spraying and were given permission to visit a malaria clinic in Kaniki, a 30-minute drive away and around 3km from the border with the Democratic Republic of Congo. Zambia shares a border with eight countries, but at 2,332 km (1,449 miles) its western border with the DRC is the longest, and much of it is dense with forest and people. It’s also where many of the high prevalence malaria areas in Zambia are located. Indeed, on the morning we visited, of the 56 people that came in seeking help, 35 were positive for malaria.

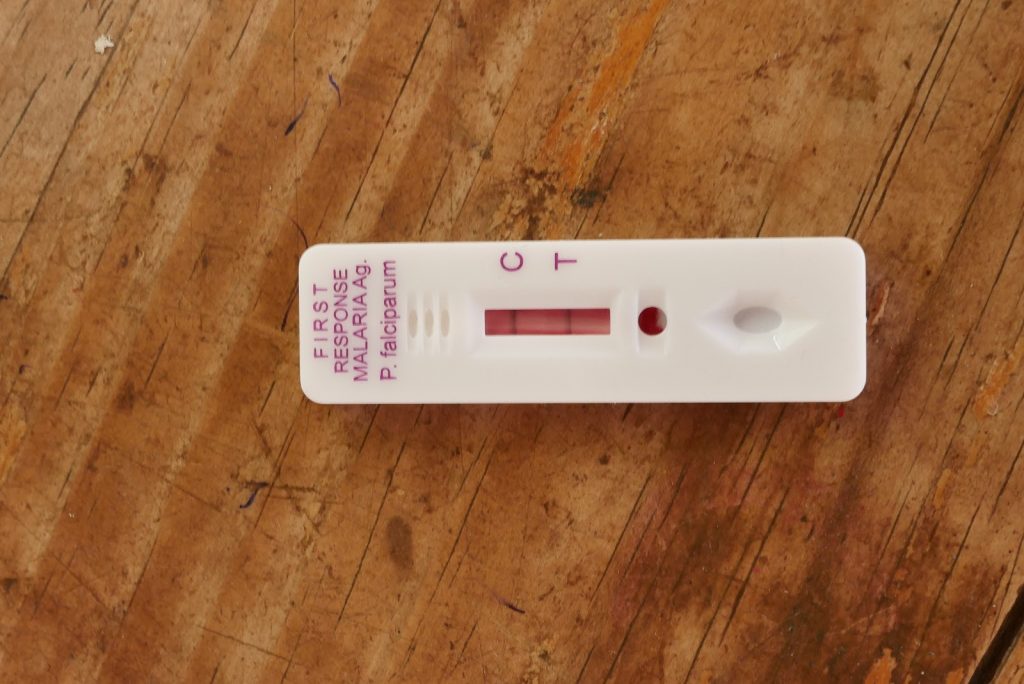

The clinic in Kaniki exemplifies how rural healthcare works in Zambia. People who have a fever or feel unwell in the morning will attend the clinic, where most healthcare and treatment is free of charge. The first triage step involves everyone getting their temperature taken and having a rapid diagnostic test (RDT) for malaria. If they are positive they are sent to one set of nurses who provide treatment, which in this clinic was coartem (artemether-lumefantrine). Those who are negative get sent to a different set of nurses who then investigate the cause of the ailment further.

This is why RDTs are so important. They are used as a frontline tool in villages to diagnose malaria and as we learnt in Namibia, are also used for reactive case detection, to find potentially asymptomatic patients who may still be transmitting the disease. We’d heard in Namibia and now in Zambia that a key pillar of malaria control is to diagnose and treat every case. In such remote settings in the absence of diagnostic labs, this can only be possible with RDTs.

That almost 60% of people who turned up to this clinic had malaria demonstrated that this was a highly prevalent malaria area. Our colleagues from NMEC had received ethical clearance to collect blood spots from some of the positive patients and our aim was to work with them to extract DNA and run it on the MinION over the following couple of days. In the end, it was straightforward and quick to collect 7 samples, which were then taken back to Ndola where our plan was to extract DNA that afternoon. We all enjoyed speaking with the health workers and nurses at the clinic and learning about the daily routine of rural healthcare.

Working in Ndola

We went back to the TDRC and Jason worked with Brenda and Rachael, two PATH scientists who’d accompanied Dan from NMEC and who were keen to learn about and get firsthand experience of our sequencing protocols. We’d wanted to try to perform the whole process in the car, from blood spot to data generation, but we had to balance this desire with the need to continue to teach people to run the kit as well as our scheduled meeting with Dr Manyando at the TDRC. We therefore decided to run the first couple of steps of our protocols where we extract DNA from the blood spots at the TDRC lab before using the car the next day to run some of the next steps.

With Jason busy extracting DNA, Isaac and I were asked to give impromptu talks to a gathered crowd of around 30 parasitologists, entomologists, clinicians and, quite unexpectedly, the head of the TDRC. The audience introduced themselves and we learnt of the TDRC’s history as one of three original WHO mandated tropical research centres started in the 1970s. (The other two are in Brazil and the Philippines). As I spoke about the project and answered questions, it was clear again that there were people keen to collaborate and that genetic sequencing was one of the technologies that people here were keen to test. Interestingly, several mosquito researchers were interested in using the technology for assaying insecticide resistance, something that we’re hoping to test in Kenya.

After our meeting we returned to our guesthouse and had a strategy meeting. We were only in Ndola until Wednesday and if we were to hope to get DNA onto the machine before we left, then it was clear that Jason, Dan, Brenda and Rachael were going to have to work into the night to get things finished in time.

The next day we visited another clinic in Ndola and asked if we could set up our mobile lab nearby. We wanted to run some of the kit and had invited people from the TDRC to visit and talk about the technology. That afternoon, under the branches of a mango tree, we ran some of our equipment (but not the sequencing machines) using only power from the Land Rover.

Another late night of work in the hotel was needed to further prepare samples for the MinION (sequencing machine). In his hotel room the following day, Jason finished the last few preparation steps and by early afternoon we were ready to run the samples collected two days previously on the MinION. Dan and his team had left earlier in the day. We’d said our thank-yous and goodbyes and had left Dan and his team with enough kit and reagents to perform the same analyses on the same samples themselves back in Lusaka.

Sequencing DNA in the back of a Land Rover

We had a few long days driving ahead of us as we needed to drive across Zambia and Tanzania to get to Kenya for our next major project of the trip. So, we were keen to get moving. With a couple of good MinION runs in Lusaka under our belt we thought it would be fun to see if it was possible to prepare and load a MinION on the backseat of the Land Rover and then run it whilst we were actually driving.

Isaac and I packed up the car, putting the middle armrest down in the back seats to attach the MinION and MinIT (a small analysis computer) to them. We have an additional battery in the car with plug sockets that we could plug the machines into. In the mid-afternoon heat Jason loaded the MinION and pressed start, all on the back seat of the Land Rover. After a few minutes we left the hotel car park and started our 2-hour drive to the Forest Inn. The MinION continued to run as we drove, generating over 1 billion bases of data by the time we got to our motel.

So, as we began our long departure from Zambia, we were content with our achievements in the country. We’d learnt about the work of NMEC, PATH and the TDRC; we’d got the MinION to work on parasite DNA in Africa; we had taught Dan and his team the basics of nanopore sequencing, leaving with them some kit to give it a go themselves, and we had generated enough data for them to start understanding nanopore data analysis. And finally, we had shown that it is indeed possible to run a genetic sequencing machine in the back of a moving Land Rover.